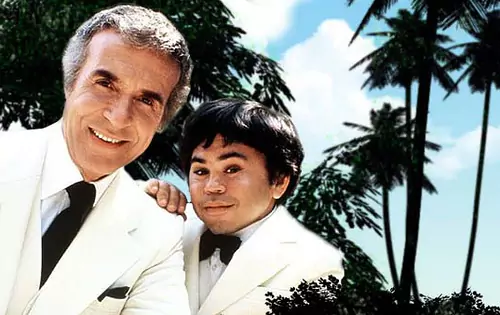

Judy Cares About… Ricardo Montalban and Herve Villachaize, the Caretakers of Fantasy Island

Being thankful for the empathy and sacrifice of caretakers

One of my favorite television programs as a young person was a show called Fantasy Island. Those old enough to remember this seventies phenomenon can recall the beauty and promise of the island, the joy of hopes realized by the guests, and the hospitality, poise and gentility of the island’s owner and manager, Mr. Roarke, played by Ricardo Montalban, and that of his assistant Tattoo, played by Herve Villachaize. Every Saturday night, the show would open with an image of Mr. Roarke’s private plane approaching the sunny Hawaiian island, joyfully heralded by Tattoo calling, “Boss, the plane! The plane!” and pointing to the sky. Then Ricardo Montalban would look into the camera with his steady, welcoming gaze, and say, “Welcome, to Fantasy Island” . The two men, looking dapper in matching white Panama style suits, and their competent staff, ready at their posts of service, would warmly welcome a new group of guests as they disembarked the private plane. As the guests took in the scene at this pristine resort, the staff would carry each one’s luggage to the assigned room. Mr. Roarke would spend a few minutes personally welcoming each guest to the island. He would confirm with the guest his or her reason for wanting to spend a week at Fantasy Island.

Most of the guests were on the island of their own initiative, and a few had received the trip as a gift from a loved one. All of the guests had one thing in common: a lifelong dream that had not yet been realized. This was their fantasy, and Fantasy Island was the place where Mr. Roarke, Tattoo, and the staff would do all in their power to see each guest’s fantasy realized. By the way, these were all fictional characters. Reality television had not advanced too far beyond The Dating Game and The Newlywed Game by the late seventies. As a preteen, I eagerly absorbed each story, as each character faced personal crises, rethought their priorities, and grew emotionally, gaining even more than their heart’s desire.

Fast forwarding to the New Millenium, I now live on an island where nearly everyone has come with the goal of seeing their life’s dream fulfilled. The “guests” who are my neighbors here in Manhattan would not use the word “fantasy” to describe their goals and aspirations, partly because the word carries more of a sexual connotation than it did thirty years ago, but also because the word “fantasy” connotes a desired object, outcome or situation that is almost unattainable and therefore separate from ordinary life, as in “fantasy” versus “reality.” A fantasy is thought to be something that might happen TO you, if you were very lucky, but probably could not have been brought about BY you. People entering the work force on my island, and in many population centers today, are not wasting time fantasizing, dreaming, or wishing for their goals to be fulfilled. They have been trained from early childhood to choose attainable goals and aspirations, and to categorize them as short-term, medium-term, and long-term, and to then start working busily and efficiently toward these goals.

Of course, success and achievement are very satisfying, and are necessary in some degree for one to make a living. I am deeply grateful to live in a country where the freedom to choose and pursue one’s own goals and aspirations is a legal right. However, I believe that when people are pressured to skip over the very necessary stage of dreaming, imagining, and fantasizing, in favor of getting on with the busy and efficient achievement of attainable goals, they suffer in various ways, and they miss out on other kinds of fulfillment that would make them feel more fully human.

The first negative outcome of a success-obsessed culture is a loss of personal uniqueness, confidence, and purpose. Many young adults arriving in New York City to attend their dream school, or to report for their first career-track job, feel that they are someone special because they were ranked in the top 10% of their high school class, or because they played the lead in their high school play, or because thy won an award back home. They quickly realize that they are surrounded by other super-high achievers, who were ranked higher at more competitive schools; have Broadway shows on their resumes; and have won more numerous and prestigious awards. This realization can be crushing and disorienting to people who have defined themselves through their achievements. This island can then seem like a cruel, confidence-shredding place, and it can be really difficult and stressful to face each day as “just another face in the crowd,” or as “nobody special.” A skilled psychotherapist or a trusted friend or family member can help someone who is feeling like “nobody special” to regain their confidence and purpose. Within a trusting relationship, the person who has lost confidence can be reminded of their intrinsic worth and value, outside of their achievements. This puts the role of accomplishments into a more healthy perspective, and frees up the person to more creatively reflect on their unique strengths and interests, and on what personal goals might make them more fulfilled and happy. Like Mr. Roarke and Tattoo, they can help someone who has lost their confidence to realize that it is not the fantasy itself that fulfills, but the personal growth that goes along with it.

Another negative by-product of a success-obsessed culture is the high incidence of anxiety and depression. Failure is depressing for everyone, but especially for those who are not accustomed to it and/or feel ashamed of it, as is the case for successful, high-functioning people. Many gifted people in their twenties and even thirties have their first-ever failure experience, and see this as an indication that they are not talented enough in their field of endeavor to succeed. They think about changing careers, and feel depressed enough about these setbacks to seek therapy for the first time. Others have a string of unbroken success, but maintain their busy lifestyles with too much reliance on adrenaline, leading to anxiety and even panic. Anxiety can feel just as strange and embarrassing to successful people as sad, depressed feelings. The anxious or depressed person needs the opportunity to examine their beliefs about themselves and about life, in a non-judgmental setting. They also need support from a therapist or trusted friend or relative, in order to process disappointment and worries, especially as these may be new experiences for them. Then they can develop resilience to setbacks and a deeper maturity, which help them to make wise decisions about their future. Another 70’s “phenom”, Edith Schaeffer, wrote that for someone to recover from tragedy and setbacks, they need someone to cry with them. People who have processed their disappointments and anxiety well, can then weather even the worst Island storm.

Success-obsessed cultures also feature a lack of connection where there should be empathy and caring. When people are obsessed with their personal success, they are not willing to sacrifice precious time and resources for relationships that don’t advance their personal goals. They become much more concerned with being “well-connected” than with having real friends. As a result, they can become deeply lonely, because they have no one with whom to share their successes and failures. They regret “using” people, and letting themselves be “used.” They almost always feel underappreciated. By contrast, the most fulfilled Island dwellers I have come to know are those who consistently place themselves in situations that demand they show empathy and caring for others. They maintain reciprocal friendships, they volunteer, they do pro bono work, and/or they participate in religious groups. They want to “give back”, which is another sign of personal maturity.

I was always fascinated by the untold stories on Fantasy Island. One guest might have had the dream of learning how to scuba dive, for example. Did that mean that the scuba instructor was a paid member of the staff, or was she perhaps another guest on the island, who had a life-long dream of teaching scuba diving on a Hawaiian island? That question leads to larger ones – were all of the people on the island guests, having their fantasies fulfilled, or were some of them staff? Were the staff members paid, or volunteer? The fee for a stay on the island was said to be some amount that was a significant amount to the guest, and in some cases as much as $50,000, but was that enough to cover all of the expenses? Did the guests’ families, or possibly a foundation, underwrite some of the costs? Mr. Roarke was supposedly endowed with magical powers. Perhaps he used those powers to magically stretch the money further. Whatever the untold story on Fantasy Island was, it involved sacrifice by someone for the sake of someone else.

Mr. Roarke and Tattoo didn’t think of Fantasy Island as primarily a place to get their own goals accomplished, but as a place to caretake, and a place to host others, leading them to then invest significantly of their time and resources for the sake of others’ fantasies. Paradoxically, spending time, emotional energy, and personal resources to advance another person’s goals and dreams can actually be more fulfilling than spending those same precious resources towards one’s own goals. A psychotherapist or trusted friend or relative can help a client to process what true success means. I care about Ricardo and Herve because in their entertaining way – remember Herve zooming around in that little white car? — they taught me a lot about fantasies, goals and the important things that shouldn’t be missed along the way.